1. Vietnam abandons pro-nuclear policy

In November 2016, the Vietnam National Assembly passed a resolution calling for the cancellation of nuclear plant construction planned in Ninh Thuan Province the central-south part of the country. Russia was expected to receive the order for the first nuclear plant in that province, and Japan the second one.

The main reason Vietnam decided to give up on nuclear power was economic. After the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident in 2011, projected construction costs for the nuclear plants rose from the initial projection of one trillion yen to 2.8 trillion yen, and projected electricity rates from nuclear power increased by a factor of about 1.6 compared to initial forecasts.2

Vietnam’s conclusion: “Nuclear power is not economically competitive.” For the construction of the plant from Japan, it had been agreed that Japan would provide preferential loans at low interest rates, and this most likely meant that government-affiliated financial institutions such as the Japan Bank for International Cooperation would be involved. But the view that Vietnam should not increase its debt to Japan any further was another reason to cancel nuclear plans.

“This is a ‘courageous withdrawal,’ “ said Le Hong Tinh, Vice Chairman of the Committee of Science, Technology and Environment, in an interview with VnExpress.3 “The growth in electricity demand is slower than expected at the time the nuclear construction plan was proposed. Power saving technology has advanced, and LNG and renewable energy are starting to become competitive. We can adequately meet domestic demand. We need to stop the projects as soon as possible before suffering any further losses.”

There is no doubt that Vietnam’s confidence in nuclear safety was shaken after the Fukushima nuclear accident, although official statements did not use that as an ostensible reason for withdrawing. There is conjecture that Vietnam had to be deferential to Japan, its biggest aid donor. Cautious comments were made one after another by domestic experts and former officials of the Communist Party of Vietnam.

Japan had been counting on nuclear exports not only to Vietnam, but also to Lithuania, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and more. But one after another the prospects have fizzled out.

Table. Japan’s nuclear export prospects fizzle out

| Vietnam | Multi-agency efforts were made with significant Japanese public tax money committed, but Vietnam cancelled plans. |

| Lithuania | Hitachi was planning nuclear exports, but nuclear plans were frozen by public referendum. |

| Turkey | Mitsubishi Heavy Industry was moving ahead on nuclear exports, but construction costs doubled, and partner Itochu Corp pulled out of the deal. MHI eventually pulled out too. |

| UK | Hitachi was planning to construct a nuclear plant in northern Wales, with total project costs of 3 trillion yen. Hitachi was calling on both Japanese and UK governments to provide funding, but decided to freeze the project in January 2019. Practically speaking, Hitachi has withdrawn. |

2. Taiwan

In January 2017, Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan (legislature) passed an amendment to its Electricity Act. The amendment states that the life of operating nuclear power plants will not be extended, and they will be decommissioned after they have reached 40 years of operation. This meant that Taiwan would no longer have nuclear power after 2025. Moreover, the amendment also stated that the renewable energy sector will have electricity deregulation in order to promote private sector participation, and eventually to increase the proportion of renewable energy from 4% then to 20% by 2025.

In Taiwan, a civic movement demanding an end to nuclear power emerged after the lifting of martial law in 1987. Mass protests were held, especially against the Lungmen Nuclear Power Plant. After the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011, mass demonstrations and public opinion against nuclear power led to a declaration in 2014 under the administration of Ma Ying-jeou that construction plans for the plant would be frozen.5 Ma Ying-jeou was with the Taiwanese National Party, which had been promoting nuclear power. The biggest reason Taiwan shifted towards abandoning nuclear power was the shock of the Fukushima accident. The First and Second Nuclear Power Plants are within 30 kilometers of the capital city Taipei, and if an accident occurs, millions of people will be affected. The cost of a disaster would be huge. Furthermore, existing nuclear power generating facilities are approaching the end of their service lives, and the disposal of radioactive waste is still a problem.

In 2018, the national policy of going nuclear free by 2025 was tested in a referendum, and there were slightly more votes against versus in favor of denuclearization policies. However, among the four nuclear power sites in Taiwan, Units 1 and 2 had already exceeded their deadline to request an extension of operations, and the local mayor near Unit 3 is opposed to any extension. In the case of Unit 4, a revised budget allocation would be needed to restart construction. Although the “no” vote for denuclearization by 2025 won by a slight margin, the basic policy of denuclearizing remained unchanged,6 and in 2019 the national government announced that there would be no change to the national policy to denuclearize.7

3. South Korea

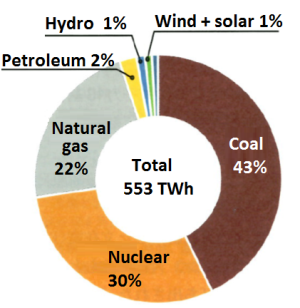

Twenty-four nuclear reactors were operating in South Korea, plus four under construction and six that were at the planning stage. Thirty percent of South Korea’s power generation came from nuclear. It was under such circumstances in 2017 that then-presidential candidate Moon Jae-in (still in office as of 2019) made the following election campaign pledges regarding nuclear power: (1) to stop construction of any reactors that were under construction, (2) to cancel any new ones being planned, (3) not renew the licenses of operating reactors, and (4) to create a roadmap to exit from nuclear power in South Korea. If he were to follow his pledges, the new Kori Unit 5 and 6 projects would be discontinued.

Fig. Korea’s electricity generation mix (2015)

Source: IEA Electricity Information 2017

President Moon Jae-in was elected with overwhelming support from voters. Once elected, at a ceremony on June 19, 2017 marking the end of operations the Kori Unit 1, South Korea’s oldest nuclear reactor, he declared that his country would exit from the era of nuclear energy. In regards to Kori Units 5 and 6, he said he “will reach a conclusion after hearing public opinion,” which was considered a retreat from his election pledges.

Construction of Kori Units 5 and 6 had reached 30% of completion, so the idea of canceling these projects was controversial. In fact, local residents were employed in their construction and compensation was being paid to the local community, so there was strong resistance to any talk of cancellation.8 Despite his pledge, President Moon Jae-in dared not make his own decision, but entrusted the fate of those projects to a public process.

Public opinions were gathered for three months starting in July 2017. A public debate committee was established, and it documented both the pro and con arguments for these nuclear projects. A first public opinion poll was conducted on 20,000 people, and by considering region, gender and ages, 500 people from the respondents were selected as a group of citizens to participate. Among them, 471 studied up in advance, then participated in a comprehensive discussion, and answered a final survey. The result was 40.5% voting for cancellation and 59.5% for restart of construction. Based on this result, the South Korean government decided to continue with construction of Kori Units 5 and 6. Besides the question about those two units, the participants were asked about the future of nuclear power. The results were 53.2% in favor of reducing, 9.7% in favor of expanding, and 35.5% in favor of maintaining the status quo with nuclear power.

The design life of Kori Units 5 and 6 is 60 years, which translates into a significant delay in the ending of nuclear energy in South Korea. On the other hand, President Moon Jae-in said he would carry out the cancellation of all new nuclear power plant construction projects and the earliest possible deactivation of Wolseong Nuclear Power Plant Unit 1. Even before it reaches its planned service life, if that reactor is confirmed to be unnecessary for the electricity supply, he will use that as a basis to take policy steps towards its decommissioning.9

FoE Japan, Kankoku: Datsu genpatsu wo motomeru hitobito no chikara (South Korea: People power demanding an end to nuclear power) Feb. 2018.

4. Germany

After the serious radioactive contamination from the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster was reported in Germany, there was growing sentiment against nuclear power. In public discussions about abandoning nuclear power, after various complications the Atomic Energy Act was amended in 2002 towards the phase-out of nuclear power under the administration of Gerhard Schroeder, who was leading a Green Party and Social Democrat (SPD) coalition. The amendment prevented the construction of new nuclear power plants, and the duration of operation of existing nuclear plants was stipulated as 32 years, so nuclear plants reaching that milestone were required to be deactivated, which would have meant a complete nuclear exit by 2022.10 However, in 2009 the second Merkel administration bowed to requests from power utilities and decided that nuclear plant operations could be extended for up to another 14 years. Accordingly, the Atomic Energy Act was amended again in October 2010.

After the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in March 2011, the subsequent Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident was reported day after day in Germany. Large demonstrations took place around the country, and there was a rise in public opinion seeking an end to nuclear energy. Chancellor Angela Merkel responded quickly. She decided on a three-month moratorium on nuclear power, and ordered the Reactor Safety Commission to perform safety inspections on all 17 nuclear plants in Germany.

That same year Merkel launched the Ethics Commission for a Safe Energy Supply. The commission met many times from April 4 to May 28, held hearings with a wide range of stakeholders, hosted dialog meetings with citizens, and then compiled a report and submitted it to the Chancellor. The report said that “the phase-out of nuclear power is possible as there are alternatives with lower risks,” recognized the phase-out of nuclear power as a chance for Germany’s development based on an energy transition and technological innovation, and proposed withdrawing from nuclear power energy promptly.

In light of this, Merkel, on June 6, 2011, made a cabinet decision to deactivate all 17 existing nuclear plants by 2022 and to switch to alternative energy. In July, the Atomic Energy Act was amended again. After watching scenes of the Fukushima nuclear accident, Merkel, a physicist, admitted that her view on nuclear power had been “too optimistic.”11

It may appear that Germany swiftly changed course in its policy toward the phase-out of nuclear power in 2011. But it is important to recognize the tremendous underlying flow of events that led to this decision on the nuclear phase-out, including the severe impacts felt after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, the rising movement against the construction of radioactive waste disposal sites, distrust in nuclear technology, the formation and rapid progress of the Green Party, and steady investments in renewable energy. Chancellor Merkel, as a realistic politician, recognized this movement toward the phase-out of nuclear power, and made it a reality by establishing the Ethics Commission and reviving the previous decision to phase out nuclear energy.

- MITSUTA Kanna, “The global tide of the end of the nuclear era: Countries withdraw from nuclear, but Japan still clings on” Imidas (January 5, 2018) in Japanese.

- VnExpress, “Majority of legislators approve halt of nuclear plans,” 10-Nov-2016.

- VnExpress, 10-Nov-2016

- Ayumi Fukakusa, “Taiwan: People Power Victory to End Nuclear Power” (FoE Japan, Sep. 2017, in Japanese).

- No Nukes Asia Forum, ed., “People in Asia Stopping Nuclear Power Plants” (September 2015), p. 88-105 (in Japanese).

- FoE Japan, Taiwan no datsugenpatsu ni matta!? Datsugenpatsu seisaku no yukue (Denuclearization in Taiwan: Wait a minute!? The direction of denuclearization policies) https://foejapan.wordpress.com/2019/01/28/taiwan-2/

- 31-Jan-2019, Mainichi Shimbun, Taiwan, datsugenpatsu hoshin wo keizoku, min’i mushi no hanpatsu mo (Taiwan, some opposition to ignoring public will and continuing with denuclearization policy).

- Interview with Korean Federation for Environmental Movement (KFEM), 23-Nov-2017.

- The Hankyoreh (newspaper), “Prospects for 1st Wolseong Nuclear Power Plant to be included in roadmap to abandon nuclear power,” 22-Jul-2017 (in Korean).

- Gen Maejima, “Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) and antinuclear policies,” in “Alternatives” (Pacific Asia Resource Center magazine).

- Politas, “Current status and topics in Germany which chose to exit from nuclear energy”(22-Jun-2015, in Japanese) http://politas.jp/features/6/article/389