Many evacuees from the nuclear accident received subsidies under what is known as a “quasi- temporary housing program” based on the Disaster Relief Act. However, the provision of relief for some 26,000 residents covered under this Act who were evacuees from the non-designated evacuation zones (so-called “voluntary evacuees”) ended in March 2017. The meager low-income rental assistance that continued thereafter was scheduled to be terminated in March 2019.

The government is also planning to terminate the housing provision in March 2019 for evacuees from areas outside “areas where returning is difficult” where evacuation orders have already been lifted, such as Kawamata, Kawauchi, Odaka Ward in Minamisoma, Katsurao, and Iitate.

Refugees from outside of evacuation areas in many cases decided to evacuate, even without compensation or support, in order to protect their children and families. The compensation finally approved in December 2011 was also small, far too low to cover expenses associated with the evacuation. Many ended up isolated and in need. Some are elderly persons, persons with disabilities, and single mothers with no one else to rely on. These facts have been confirmed by multiple surveys.

What challenges do evacuees face?

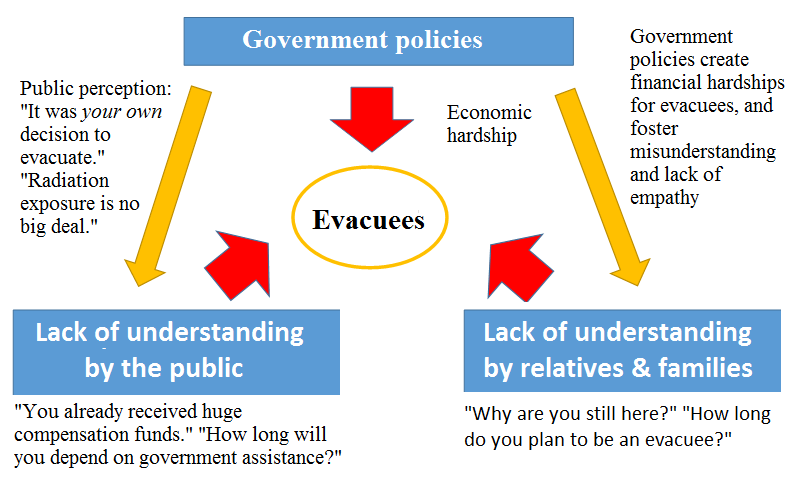

The termination of housing provision, the only government support evacuees received, takes away their basis for living. Nevertheless, 78% of evacuees living outside of Fukushima Prefecture still chose to continue living in evacuation.1 The policy of the national and Fukushima prefectural government to discontinue support conveys a message to the surrounding community that there is no need to evacuate anymore. This has resulted in a lack of empathy for victims, who end up being criticized for depending on compensation (Fig. 1). It is thought that this context is also resulting in the observed problem of bullying of children from evacuee households.

Fig. 1 What challenges do evacuees face?

Surveys of evacuees reveal economic hardship and suffering (Tokyo, Niigata Prefecture, Yamagata Prefecture)

The largest number of evacuees lives in Tokyo. In May 2017, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government released the results of a survey targeting evacuees living in Tokyo, including evacuees from inside and outside evacuation zones, and evacuees from outside of Fukushima.2 It revealed that in the majority of cases the head of the household was over 60 years old, that there was a high and growing proportion of single- person households, and that more than 47% of all the householders were unemployed.

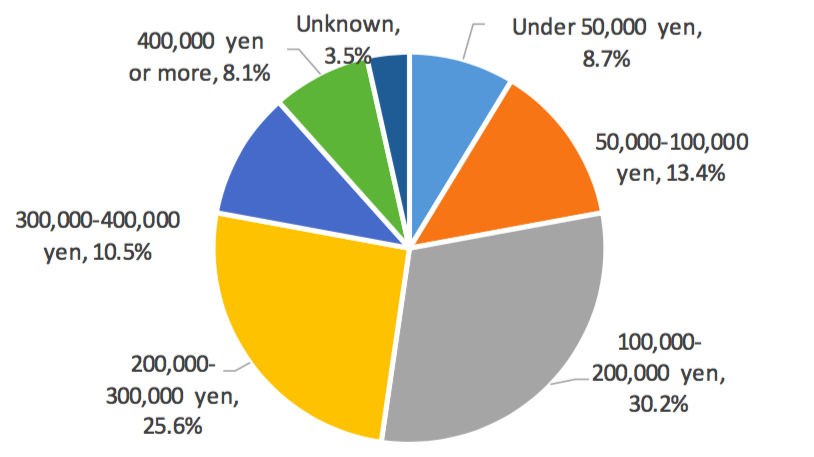

The Tokyo Metropolitan Government also conducted a survey of evacuees whose provision of housing ended in March 2017.3 It showed that 22% of households had a monthly income of 100,000 yen or less, and for the majority of households it was 200,000 yen or less (Fig. 2), which in Tokyo would mean living with significant economic hardship. Additionally, 16.5% of evacuee respondents said that they had no one to contact or from whom they seek advice day to day.

Fig. 2. Monthly incomes of evacuees outside the area

Source: Tokyo “Results of survey for evacuees from Fukushima Prefecture, for which the provision of temporary housing was ended at the end of March 2017,” October 11, 2017.

As part of a review by Niigata Prefecture regarding the nuclear accident, Associate Prof. Wakana Takahashi of Utsunomiya University conducted a study based on statements in a lawsuit seeking compensation for the nuclear accident, from all 237 households of the plaintiffs who had evacuated to Niigata Prefecture.4 The study found that living in prolonged evacuation conditions, people were having a difficult time, with more than 70% voicing feelings of “sadness and internal struggles over losing their hometown.” Among the evacuees who were from outside the official evacuation areas, 78.7% cited economic hardships. More than 60% of those evacuees cited “transportation expenses for meeting/visiting” and “increased food and utilities expenses associated with maintaining two households” as reasons for the increased economic hardship.

The review by Niigata Prefecture also made the following observations:5

- The evacuation is resulting in smaller household sizes (number of members). Single- and two-person households increased (from 32.4% before disaster to 50.2% at time of survey), and three-person or more households decreased (from 67.5% to 49.9%).

- The number of three-generation households has also decreased sharply (from 15.3% to 6.4%), and families have been dispersed as a result of the evacuation process.

- Evacuation has reduced regular employment, self-employment and family employment, and increased non-regular employment including part-time work, as well as unemployment.

- As a result of evacuation, the monthly average household income decreased by 105,000 yen (from 367,000 yen before evacuation to 262,000 yen at time of survey).

- Many evacuees are feeling isolated as a result of a weakening of the human connections they once had through long-term relationships, friends and acquaintances, and weaker connections with their neighborhoods and communities.

Yamagata Prefecture has been conducting an ongoing survey of people who evacuated to live there. In the October 2012 survey, nearly 40% were mother and child evacuees. A survey in July 2018 found that the number of mother and child households had decreased, but still accounted for 20%.6 The reasons for continuing the evacuation included “concern about the impacts of radiation” (43.5%), and having trouble due to lack of funds to cover the cost of living (64%).

The three surveys cited here tell of the difficulties faced by evacuees due to financial hardships and mental suffering. One would expect the Reconstruction Agency to be investigating the situation of all evacuees and taking steps to address problems, but the Reconstruction Agency is not surveying their situation at all.

Evacuees call for help

The Hinan no Kyodo Center (Cooperation Center for 3.11) is a support center for evacuees in Tokyo, and FoE Japan serves as its secretariat. It has received many inquiries from evacuees facing difficulties and seeking advice. Many of their inquiries relate to housing and to life in general. Below are some examples:

- Evacuees cannot afford the rent for housing, even if they move to a cheaper place.

- An evacuee wanted to move into public housing provided by the local government, but gave up because of overly strict criteria.

- A mother and child evacuated together, but divorce mediation is underway, and one partner is receiving sick pay and being treated for illness. Normally, both partners’ income is included in income calculations until the divorce is finalized. As a result, the “household” income exceeds income criteria, so the mother could no receive a rent subsidy.

- Living conditions are getting worse and the family is finding it difficult to pay the rent. They have run out of money.

- An evacuee applied for welfare but was rejected for various reasons (having living arrangements in both Tokyo and Fukushima, owning a car to care for parents in Fukushima, cannot move due to concerns the children may be bullied in the new location, etc.).

The government’s policy of discontinuing support for evacuees not only forces evacuees further into economic hardship, but also conveys an implicit message that the nuclear disaster is over, so evacuees should be able to stop relying on assistance. As a result, the community is less understanding and supportive, and this all puts additional strain on evacuees.

New assistance schemes needed for evacuees

The Act on Assistance for Children and Nuclear Disaster Victims, which entered into force in 2012, specifies that the national government will provide adequate assistance to victims who have made the decision to stay, evacuate and or return. Article 9 of the Act specifies that the government is to secure their housing. The basic policy for implementation of the Act adopted in October 2013, including a clause about facilitating entry into public housing, which stipulated that income and hardship criteria be relaxed so that evacuees could enter public housing units. However, the concrete measures are left up to the municipalities to deal with. And as indicated above, evacuees can fall through the cracks and end up with serious hardships and in dire situations.

The government has been strongly promoting national nuclear energy policies, so it should also be responsible for putting in place solid legislation, programs, and implementation structures to assist evacuees.

- Evacuees Residential Community Coordination Division, Fukushima Prefecture, April 2017 (in Japanese).

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government, “Results of sixth survey of evacuees in Tokyo metropolitan area,” May 2017. Survey period Feb 16 to Mar 10 (2017), total 837 responses (41.4% response rate).

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government “Results of survey of evacuees from Fukushima Prefecture for whom the provision of temporary housing ended at end of March 2017,” Oct. 11, 2017. Target was households who could be reached by postal mail, among 570 households who had left their temporary housing, among evacuees from Fukushima Prefecture whose provision of temporary housing ended by the end of March 2017 (629 families lived in the temporary housing provided by the city as of April 1, 2016). Total 172 responses (response rate: 30.2%).

- Documents from fifth meeting of Niigata Prefecture review committee (livelihood subcommittee) on health and livelihood impacts of nuclear plant accident (Dec. 27, 2018).

- Documents from second meeting of Niigata Prefecture review committee (livelihood subcommittee) on health and livelihood impacts of nuclear plant accident (Dec. 23, 2018). Survey of 1,174 households and heads of households who evacuated to Niigata Prefecture and are there now, or evacuated there but are currently living in another prefecture, plus another 192 adults and 122 junior and high school students.

- September 2018, Survey of evacuees (Evacuee Support Team, Yamagata Prefecture Wide Area Assistance Headquarters).